It’s hard to tell a friend, even a good friend, that you don’t recognize the strange and frightened woman who stares back at you in the mirror every day. How you have prayed with desperation for relief from the trauma that arrived with such ferocity.

Illustration by Hokyoung Kim

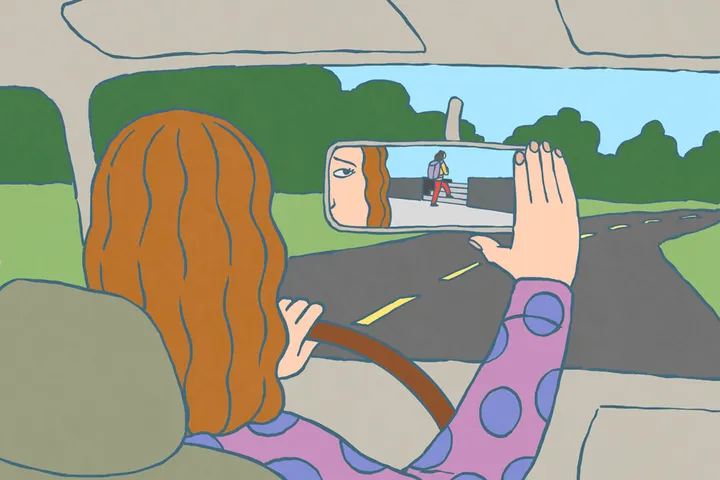

My friend Christie and were sitting in the shade, eating lunch, and our conversation danced lightly around the darkness of my severe anxiety over the previous year. I had avoided driving long distances as much as possible, feeling panicked even on short drives to church or to pick up my daughter at Panera.

When I was 15, my favorite mentor and his entire family died in a fiery car crash while on vacation, after a tractor trailer hit their vehicle. Within five years, a childhood friend lost his life in a motorcycle accident, and just months before my wedding, my grandparents were killed in a car accident when struck by an oncoming truck. I had never fully processed these losses, which finally came to a head in my 40s.

Christie and I hadn’t seen each other for over a year when we met at Longwood Gardens on a warm September afternoon. We live hours apart in different states, but the lure of the late summer blooms and the promise of Christie’s companionship led me to rethink my moratorium on driving the distance. I thought I was ready to gently expand my boundaries. But on the long drive, a troubling memory resurfaced—one of a violent event I had unintentionally viewed on television once. I momentarily drifted lanes as I drove. This memory was just one of many threads in a deep web of unresolved trauma from which I had gingerly tried to pick myself free that year. Alone in the car, I asked God aloud to pull this memory from the darkness and heal it with His light. I turned my attention again to the drive, unsettled and disappointed at this interruption.

When I arrived, Christie and I stumbled through conversation. Since we had seen each other last, she had launched a child into adulthood, moved her in-laws into her home, and written two books. Her life had moved in a recognizable direction for women our age. For me, meanwhile, all of the unpredictability, fear, disconnection, and chaos that arrived in 2020 seemed to have triggered every unprocessed traumatic event I’d experienced as a child and young adult. A fear of loss or sudden abandonment by those I loved, whether by accident or otherwise, consumed my thoughts.

The anxiety culminated one night, when I woke from a deep sleep with a racing heart, terrifying intrusive thoughts, and a sense of dread that defies description. I shot straight up in bed and shook my husband awake, saying “Something’s wrong” while my body shook uncontrollably. After hours of trying to calm my mind and body, I eventually fell into a fitful sleep.

Every day thereafter became a battle of intrusive thoughts and anxiety. Leaving home, attending public events, teaching, and writing were lost to me in varying degrees during those long months as I tried to make sense of what happened to me. I clung to the smallest threads of normalcy and tried to reclaim my life in incremental steps.

As Christie and I chatted, I inwardly grieved the loss of my life as I knew it. Our conversation turned to books, but even my reading life had shrunk dramatically when books I previously enjoyed caused me discomfort. Only one, Henri Nouwen’s The Inner Voice of Love, became an anchor that tethered me to something solid and true, and I read it on repeat that year. As a writer, I found the disappearance of my own words to be a powerful blow, but the additional loss of my rich reading life wrenched something vital from me.

Christie had recently read C. S. Lewis’s The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, a children’s book from the Chronicles of Narnia series. In it, the main character Eustace transforms from a boy into a dragon because of the “greedy, dragonish thoughts in his heart.” The dragon overtakes Eustace’s humanity on the outside, but on the inside, he longs to be the boy he once was. One moonless night, the Great Lion Aslan, illuminated in a pool of light, appears to the boy/dragon Eustace.

Aslan beckons, and Eustace follows him to a well, where Aslan tells him to undress before bathing in the water. Eustace tries to scratch off his dragon skin, but he finds that beneath one layer of dragon skin is another layer and another and another. Finally, Eustace surrenders to Aslan and allows the Great Lion to pierce him and claw the final layer of dragon skin from him to reveal the tender boy underneath. Aslan alone holds the power to make Eustace whole.

“The very first tear he made was so deep that I thought it had gone right into my heart … it hurt worse than anything I’ve ever felt,” says Eustace.

I blinked back tears when Christie reached this part of the story. It was reminiscent of every painful memory I tried to heal and purge from my mind, only to discover another memory lurking beneath it. It hurt to heal from the deep wounds of my past when I quit ignoring, buffering, and bandaiding them. I didn’t want to revisit the accidents, the unpredictability of loss, or the fear it introduced to my life. But it kept me from living healthy and whole in the present. Facing all that was unresolved in me and fully processing it in a healthy, Christ-centered way hurt nearly as much as the initial wounding.

“You need to let your wounds go down to your heart. Then you can live them through and discover that they will not destroy you. Your heart is greater than your wounds,” writes Nouwen. I’d underlined and returned to these words in The Inner Voice of Love often that year. The heart Nouwen describes, one that can absorb the pain of life’s suffering, is a heart that knows, receives, and surrenders to the love of Christ. Christ’s love reveals all that is hidden, all that keeps us bound and unable to move forward. The real work of restoration and healing begins when our fears, losses, anxieties, sins, and individual traumas are laid bare.

The next evening, I sat under a sunset sky and read The Voyage of the Dawn Treader for myself. I skipped immediately to Eustace’s transformation, and I cried all over again. I recognized where I had spent so much energy and effort to heal as I ripped through layer after layer of past pain. I also recognized where I had surrendered it to Christ when my inner resources were insufficient for the healing ahead. All this time I expected surrender to come with a sense of relief, but like Eustace, the tear that revealed the tender woman underneath hurt “worse than anything I’d ever felt.”

Healing can hurt, but we’re made new in the process. It’s painful to ask God to reveal the source of our deepest wounds—to allow Him to love our most wounded places, and trust His guidance for resources and relationships that help healing take place. It’s uncomfortable to face the things we’ve suppressed or hidden, but our trauma, anxiety, and pain aren’t hidden from God. When I grow frustrated at the slow, painful process of healing, when I long to be fully whole with no lingering layers, I remember Lewis’s words at the end of this chapter. Eustace was not a different boy overnight: “He began to be a different boy. He had relapses,” Lewis writes. “But most of those I shall not notice. The cure had begun.”