For the first six years I lived in New Jersey, I didn’t know that Natirar existed. Once a private residence, the bucolic 500 acre park near my home was eventually sold to the county. That purchase made the grounds available to the public for hiking, picnicking, fishing, and cheering on runners at high school cross country meets.

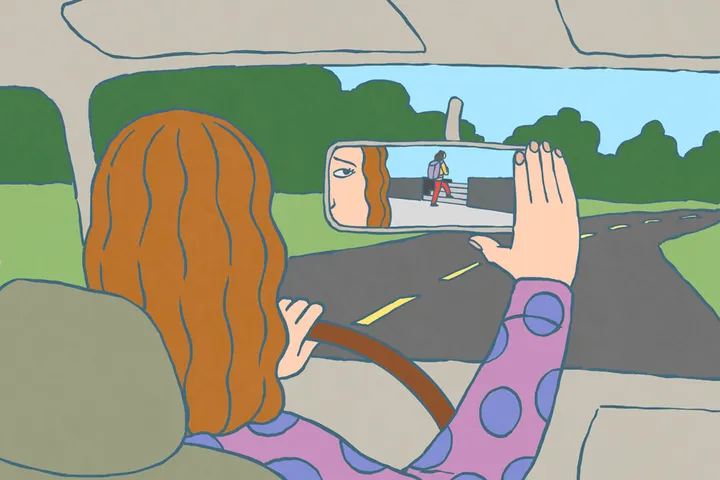

Illustration by Adam Cruft

A girlfriend and I recently met at Natirar and discovered a parking lot full of fellow walkers, runners, and hikers. As we walked, Micha mentioned she had just returned from a weekend at a friend’s newly purchased farm. This woman and her husband relocated from another state to act as caretakers of the land, restoring the farm, gardens, and the farmhouse itself, and creating a place for others to retreat. Author Christie Purifoy calls this “placemaking,” a form of creation care in which we cultivate places of comfort, beauty, and peace not only for our own sake, but also for the sake of others.

In fact, Christie and her family have done something similar—they’ve lovingly resurrected the gardens at Maplehurst, their Pennsylvania farmhouse, and every spring and fall they invite community members to enjoy the land they cultivate. Maplehurst is a sacred space for connecting with others in a setting of natural beauty.

For those of us who live in apartments, townhouses, or neighborhoods with postage-stamp yards, it may seem as if our attempts to care for the earth are too insignificant to make a difference. Our efforts can feel like more trouble than they’re worth when we don’t directly see the impact. What’s more, many people live in communities in which hands-on creation care is nearly impossible, where unspoiled places of beauty or cultivation are hard to come by. Places like Natirar, a suburban vegetable patch, or revitalized private farmland are often inaccessible to urban, economically depressed, and marginalized communities.

And yet, even these kinds of places need care. I recently learned that my county has partnered with a private buyer to develop a portion of Natirar’s acreage into a luxury hotel and million-dollar homes. I don’t know if the renovation will impact the nature trails or running paths. It likely won’t bother our community too much—most of us can sit in our tree-lined suburban backyards and not worry about it. But I do wonder why we continue to lose quiet, green spaces where deer roam as frequently as dogs and walkers. I worry about what we value when an unattainable-to-most luxury supplants the real riches of communal gathering, creation, and beauty.

While most of us will never be able to buy a farm, I admire the act of placemaking as one way to faithfully and actively care for our world. Creation care is about choosing to love the earth in ways that contribute to restoration. It’s a choice to steward our time, money, and other resources in respect to the earth and every creature on it. For some, that care involves placemaking. For others, the practice includes recycling, planting a garden, volunteering to clean up litter, or living a more sustainable lifestyle with less consumption.

Author Andrew Peterson writes, “The way we shape our cities, towns, infrastructure, and homes is a reflection of what we believe to be true about human flourishing (and creation’s flourishing) as children of God.”

As Christians, we must ask ourselves what we believe about creation’s flourishing, especially as it relates to our fellow humans. We probably know how we should answer, but are we living it? This is a question each of us can ask ourselves in the context of our own living situation.

Will we be caretakers, as God intended human beings to be (Genesis 2:15)? Will we value creation’s flourishing, and as a result, human flourishing? Will we steward our resources toward restoration? However we choose to take up this calling, we can do so in the joy of knowing this: We don’t labor alone. We join God in His work of making all things new.