My shoulder woke me, a throb emanating from deep in the socket where ligament met bone. I rolled onto my back and stared at the ceiling, knowing the pain would keep me awake for some time. As I massaged my shoulder in an attempt to reduce the ache, my mind ran through a familiar litany of midnight prayers, none of which lessened my rising anxiety. My repeated petitions for healing had gone unanswered. I listened to the night sounds around me, wondering if I’d have to live with this recurring pain forever.

I had significantly damaged my shoulder months before, when I was rescuing my dog Jack from being hit by a vehicle. While off-leash on our property, Jack spotted another dog and ran into the road as cars approached. Scrambling, I lunged for him, grabbed his collar, and pulled him to safety. In his excitement, he lurched forward, pulled me off my feet, and dragged me across our wet lawn. The accident wrenched my shoulder, tearing multiple ligaments, and resulted in a serious injury to a vital joint. When recounting the story later to friends, I asked one question over and over: “Why didn’t I just let go?” I instinctually tightened my hold on Jack out of fear for what might happen and out of a desire to save him. I was simply unable to let go.

As I lay awake in fitful prayer, my mind drifted back to Jacob’s experience of wrestling with God on Mount Peniel. I’d reread Genesis 32 a few days prior, and the details felt fresh and alive to me. It’s a peculiar account, imbued with desire, brokenness, divine intervention, and mystery. I’d known the story since childhood, but as an adult, I saw it as something more than a simple battle of wills; it was a cry for healing.

Like Jacob, I have experienced brokenness—and I’ve exchanged my identity for a new one in Christ. But throughout this painful process of transformation, I feared that if I didn’t maintain a tight grip and exercise some element of control over the situation, an encounter with God would leave me injured, alone, and with a permanent “limp”—a constant reminder of my own weakness.

When the angel visited him in the night, Jacob was preparing to face his brother Esau, the one from whom he’d stolen their father’s blessing and the elder son’s birthright decades before. As was often the case in biblical times, Jacob’s name defined his identity, and he fully lived up to its meaning of “supplanter,” one who schemes to achieve the upper hand. As he camped and waited for Esau to come and exact his revenge, there appeared a “man” whom Jacob recognized as God Himself—and the two engaged in a physical struggle. They wrestled for hours, and Jacob refused to quit, even when the man demanded to be let go before dawn.

My mind drifted back to Jacob’s experience of wrestling with God. Now I saw it as something more than a simple battle of wills; it was a cry for healing.

It wasn’t until he touched the joint of Jacob’s hip, wrenching ligament from muscle and bone that the man told Jacob to let him go. I simply cannot imagine the agony Jacob was in during those pre-dawn hours. Yet despite the pain, he wrestled on, demanding more than he deserved—a blessing from the Lord. Jacob came away with a new name as well as a constant reminder of his humanity, his imperfection, and his inability to experience God without being viscerally, bodily changed.

The injury itself is an important aspect of the story; however, scholars differ on their interpretation of it. Some believe his leg simply came out of joint; others, that the femur (thigh bone) itself was affected. And Jewish tradition argues that the injury was to the sciatic nerve, which passes through the hip socket and down the leg. That’s why Jewish law forbids observant Jews to eat this part of an animal, called the gid hanasheh (“displaced tendon”), in remembrance of Jacob’s struggle.

I cannot imagine the agony Jacob was in during those pre-dawn hours. Yet despite the pain, he wrestled on, demanding more than he deserved—a blessing from the Lord.

The gid hanasheh energizes the lower half of the body and allows it to act. If the nerve is displaced or damaged, one’s ability to connect head, heart, and body is deeply affected. Some Jewish mystics even argue that this area of the thigh is where the source of lust and desire reside. The root word in gid hanasheh—the Hebrew word nasheh—means “forgetting or forgetfulness.” When Jacob’s desire for power and control was aroused, when he was poised to grasp and scheme, he forgot who he was and what God had promised him. His bodily actions were weakened by this forgetfulness and reduced by his own crooked wants. That’s what God broke after the night-long struggle, and at the end of it all, Jacob’s mind and heart were free. His body, however, was a different story.

Since I’ve had my own experience with a damaged joint, it’s been hard to accept I can no longer function in the way I did before. My strength is gone, my mobility reduced, and pain is a constant companion. And that’s not going to change any time soon, which means my head and heart must help my body learn a new way of being. For Jacob, this involved a severing of his own desires and a greater dependence on God. Perhaps the same is true for me as well.

I have wrestled with God over so many things, and throughout each battle, I have relearned the same lesson: Compared to the Lord’s might, my own strength is feeble and insignificant. That’s why I need the transformative power of a God who will redeem my desires, call me by a new name, and allow me to push and pull against Him until I am changed.

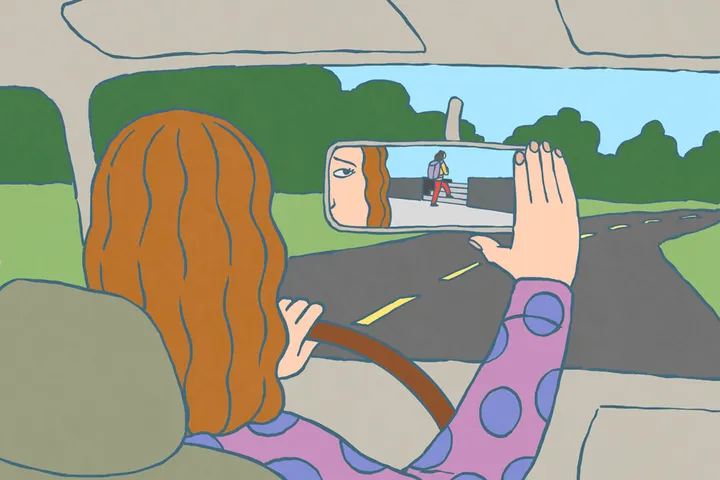

Illustration by Adam Cruft