Peter Dudnik stood and faced the back of the van, gripping the driver and passenger seat to balance himself as the vehicle careened towards the city of Slavyansk. Our destination is a city in eastern Ukraine, 160 km from the Russian border. Although the population is nearly 120,000, the town seems smaller, nestled, quiet and unassuming, amongst the lush and overgrown grassland.

Preparing himself for the twists and turns, a pastor of Good News Church told the ministry team about his home city. With the help of a translator, he spoke slowly and thoughtfully.

“There was a sense of dread hanging over our town.”

“It is difficult to introduce you to our city without telling you about the events that occurred a couple of years ago. Because we are not the same now as we were before 2014.”

In April of that year, not long after the Winter Olympics in Sochi, pro-Russian separatists invaded populated regions of eastern Ukraine, specifically the cities of Donetsk, Horlivka, and Luhansk. “The conflict was close to our city,” Peter explained. “There was a sense of dread hanging over our town. People were asking rather large questions about life, God, and faith.” But no matter how worried they were or how close the conflict came, the thought of it reaching their city was still too far-fetched.

But the conflict did come to their doorstep on April 12, 2014. Tanks and armored vehicles rolled into the city, with troops of separatist rebels behind them. The insurgents strategically seized control of government buildings and police stations, effectively taking command of the town.

After a 48-hour ultimatum made to leave the city was ignored, the Ukrainian government was forced to take action and attempted to regain control of the city. The threat of violence displaced half of the town of Slavyansk, as almost 60,000 people fled to nearby cities for safety.

The insurgents occupied Slavyansk for nearly three months. Then, on the night of July 5th, they left the city in the dead of night, as unexpectedly as they’d come. When I asked Peter why any of the events happened in the first place, he closed his eyes and slowly shook his head, still baffled by the mysteries. But through the hardship and terror his city experienced, where explanations fall short, he held on to a silver lining that informs and demands action: “We needed to know what it felt like to be refugees.”

The threat of violence displaced half of the town of Slavyansk, as almost 60,000 people fled to nearby cities for safety.

***

Our first stop in Slavyansk was a community center that had been built by Good News Church. As we arrived, we could see a large playground filled with children and rows of clotheslines weighed down by garments swaying in the breeze. Inside the center, there were just as many kids, some swarming around us, excited to see new faces, and others nonplussed, keeping to themselves in their rooms.

During the siege in Slavyansk, although many families were forced to stay behind because of financial difficulties, they did not want to keep their children close to the danger. Peter remembers his own child running into their room after every loud noise, too scared to sleep or be alone. “They were scarred from experiences that they should never have at that age. Words they should never know, like ‘shellings’ or ‘explosions.’”

As the occupation ended in Slavyansk and the townspeople gradually all returned home, the same afflictions occurring in surrounding regions became more obvious. The struggles of others nearby could no longer be ignored.

Peter and his church had always been involved in programs to help children, specifically in foster care and adoption. So when the city of Slavyansk began taking in children from other cities that are close to or inside the combat zone, Peter’s church worked to find a safe home for every child that needed one. “It was as if God had been preparing us for years to be able to meet a need in this crisis. We just needed help seeing it too.”

***

A couple hours away from Slavyansk is the much smaller town of Avdiivka, a city that is a stone’s throw from the combat. At around 5 p.m., the townspeople can hear the combat resuming in Donetsk just a few miles away. The explosions and gunshots are faint but piercing. Parts of Avdiivka have been damaged in the fighting, with gaping holes in apartment buildings and craters in roads and fields.

But life must continue even amidst the looming threats. Among the ruins of apartment buildings are families still living in rooms that have not yet been hit. Planks have been placed across windows to provide reinforcement. Orthodox icons rest on window sills as a prayer for protection. Children are riding their bikes, although they have been told to stay on the road because of the possibility of explosive devices in fields nearby.

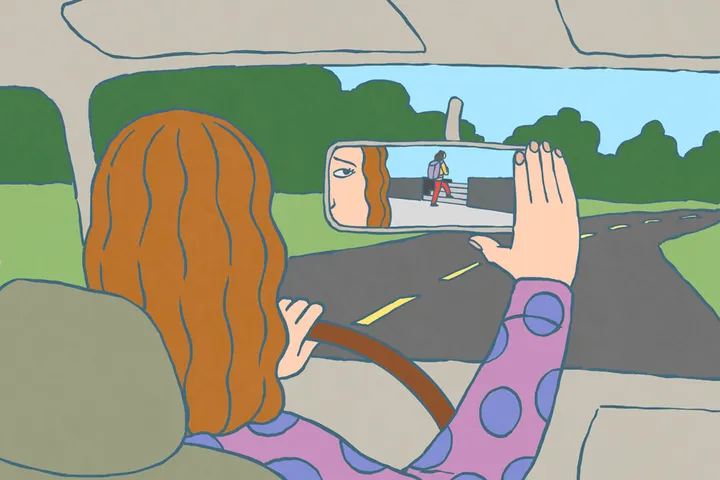

Peter vividly remembers fears like these when the insurgents arrived in Slavyansk two years prior. Tens of thousands of his neighbors fled; many who left the city, thinking they’d be gone just a few days, took only what they were wearing and little else. Peter had felt helpless. “As a church, what could we possibly do? We questioned God frequently, asking why this was happening to us. Why wasn’t He doing anything?”

That was when Peter and members of his church turned the question around and began asking themselves the same thing. As the hands and feet of Jesus, what could they do? Before fleeing with most of the townspeople, members of Peter’s church decided to transport to safety those who could not physically leave on their own.

Once it was finally safe to return to Slavyansk, their attention turned to other areas near or in conflict zones. In Avdiivka, people were experiencing the same fear those in Slavyansk felt. Despite the façade of normalcy, Peter recognized the underlying dread on each of the faces he encountered.

“I no longer want to flee the danger. I want to face it with them.”

The aid Peter’s church members had started in their own city grew in both size and purpose. Not only did they transport and provide food for those in immediate danger, but the church also created 28 mission teams to live and work along the front lines, serving wherever needed. They provide after-school programs for children, facilitate church services and Bible studies, and help repair damaged homes and apartments.

Though Peter himself is not Orthodox, in 2015 the Ukrainian Orthodox Church awarded him a medal inscribed, “For the sacrifice and love of Ukraine.” Altogether he and his team had evacuated over 16,000 people away from conflict zones. There has even been a term spreading in that part of Ukraine—“Hero Pastors”—referring to those who have braved danger to serve others.

But Peter doesn’t think much about it, nor does he feel special. He would offer that oftentimes it is through our darkest moments that our compassion for the suffering of others grow. “Not only do I feel more empathy towards them, but I feel closer to them. I no longer want to flee the danger. I want to face it with them.”

Nearly four years have passed since the initial invasion, and fear and danger persist. But thanks to Peter and the community at Good News Church, love persists as well.