Tim, put the mushroom down now!”

Although I couldn’t see Vasya, his voice echoed through the forest. “Put the mushroom down, and don’t touch anything else.”

Before I could spot him, both of the fluorescent white mushrooms landed back on the forest floor. Vasya, one of my best friends during my stay in Russia, hustled over to me and explained the particular fungus I collected was especially poisonous. “Most mushrooms that are bright and vivid are dangerous—you must be careful,” he explained, almost scolding.

It was a Saturday morning, and my wife and I were on a weekend getaway with a small group of new friends outside Moscow, our new home as missionaries. This was our first break after months of arduous Russian language studies and cultural acclimation.

After I’d sanitized my hands excessively, Vasya gave us a crash course in mushrooms, pointing out the varieties that are safe to eat and others that must be avoided. We decided that picking blueberries might be slightly less life-threatening: If it’s small, round, and blue, you pick it.

Multitudes of bright berries dotted the ground, their patches blanketing most of the forest, taking advantage of every moment of the all-too-brief summer. While we picked, our group discussed the differences between blueberries in the US versus Russia, as well as differences in outdoor hobbies. As time passed, translating from English to Russian and back again became more of a chore, and eventually we stopped almost entirely.

Beth and I soon were left alone, our friends laughing and animated in the distance. Discouraging questions began to creep into our discussion. Were we wanted here? Would our friends have had a better time without us?

As strangers in a different land, we picked up a common paranoia: When you don’t understand the language, everybody is talking about you. Laughing at you. Upset at you. Annoyed by you. Our friends, we were certain, were making fun of us.

Were we wanted here? Would our friends have had a better time without us?

For lunch, we met with an elderly couple who lived nearby in the village—the owners of the dacha we would stay in for the weekend. They greeted Beth and me warmly—a generosity that only grew when our friends explained we were Americans studying Russian in Moscow. Olya, the matriarch, eagerly described each dish as she prepared the food. She was especially boastful about her strawberry jam and led us to her underground cellar, where various preserved and pickled foods were kept.

As we ate together outside, our hosts were eager to hear about our progress with the Russian language. They shared cultural adages and lines of poetry to remember, and when Olya explained the history of the Tver region, our friends began asking questions as well. They too knew little about the area and were eagerly listening and learning.

We left with all the jars of strawberry jam we could carry, as well as an invitation to celebrate the New Year with them.

Late in the afternoon, Andrey, an acquaintance in the group, insisted I join him and a couple others in a duck hunt. Andrey’s English consisted of various movie quotes and profanity. Despite the language barrier, I looked forward to this time as an opportunity not only to practice my Russian but also to get to know the new faces on the trip.

The motorboat’s roar and the wind pelting our faces kept us quiet as we rode up the river. While Andrey looked for the perfect spot, we all were content to take in the views: The sun was just barely beginning to set, creating a vibrant and colorful spectacle in the sky.

The sun was just barely beginning to set, creating a vibrant and colorful spectacle in the sky.

About halfway to our location, the motor coughed, sputtered smoke, and died. Our small boat gradually came to a stop in the middle of the river. The three people on the boat with me immediately jumped up to troubleshoot the problem, speaking quickly and impatiently. Occasionally Andrey would turn to me and bark, “Don’t worry,” and that would be the extent of English spoken. I was able to understand a word here and there in Russian, but my basic vocabulary was no match for their technical terms.

Helpless and useless, I stood as far out of the way as possible. Eventually, the motor worked long enough to get us to the shore, and were able to walk back to the others in our group.

Midday on Sunday we began our trip back to Moscow. As the lush bright-green forest receded into rolling hills and grassland, we passed the occasional group of small and colorful dachas.

Before reaching any major highways, our friends pulled the car to the side of the road beside several hardwood tables and canopies. There was no other sign of civilization for miles behind or in front of us.

“If you want, we are getting souvenirs before we go home,” Vasya announced while walking towards the structures with the rest of our group.

I was perplexed. How would anybody find this place if they didn’t already know it was here?

There was no other sign of civilization for miles behind or in front of us.

“Souvenirs?” Beth asked. “Did I hear that right?”

With our curiosity piqued, Beth and I followed Vasya to the stands lining the road. Watching as our friends negotiated prices for trinkets and bags of dried fish, I had the simplest but most gratifying realization: This souvenir shop was meant for other Russians. We were all tourists here.

Every one of us on this trip was out of place. Our relationships did not depend on my being able to pick non-lethal mushrooms or having a perfect (or even rudimentary) grasp of the language. Our friends were patient with us because they were precisely that—friends. They explained the ins and outs of mushrooms because they were excited to share a hobby. What really mattered was the shared experience and opportunity to be in community together—all of us strangers seeking to be loved and understood.

This mundane event would sustain the next two years of my life in Russia. The days I was at my worst were the days when I felt I didn’t belong. Days I wondered if it mattered at all that I was there. These were feelings that, as part of a privileged majority back home, I’d never had to work through.

There were days my doubts still got the best of me, and there were days I still wanted to drop everything and leave Russia behind. But what makes me miss our time in Moscow— our apartment, and our weekends in the countryside—was the bond we had with our friends. And the same is true now that I’m back in the United States.

We don’t need to be in unfamiliar surroundings to find moments of alienation. The comfort and certainty of our home culture cannot completely protect us from these experiences. And as Christians, we should expect this discomfort. But we should also realize solace is found when we strive to build community as the body of Christ, working together to “stimulate one another to love and good deeds, not forsaking our own assembling together… but encouraging one another” (Hebrews 10:24-25). It’s there we catch glimpses of a place where we truly belong.

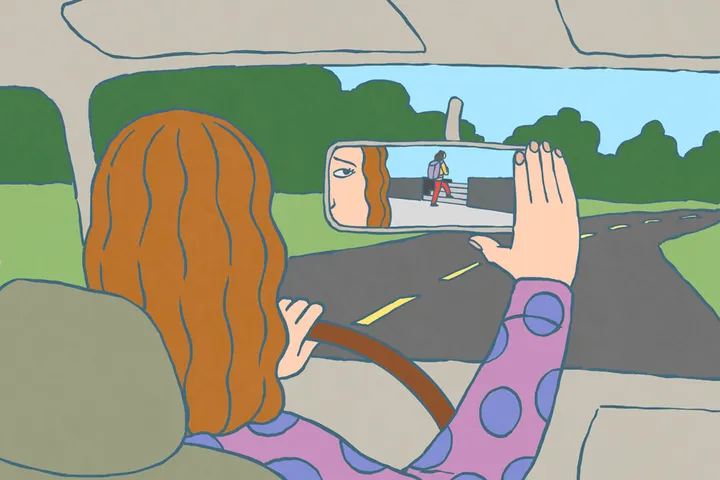

Illustration by Jeff Gregory