If there’s a hazard to growing up in church, it’s this: You can hear Bible teaching for so long that you become numb to it. You drift through world-upending ideas in a sort of waking drowse, hearing words old and familiar and mistaking them as “comfy” when they should often seem alarming or radical. When the Bible becomes part of the furniture, as it were—simply the stories we were raised with—we miss the joy of wrestling with them. Which really means these stories can’t wrestle with us. Yet even a cursory read of the Gospels should disabuse us of any notion that Jesus came to make us feel comfortable. As it turns out, Jesus had some pretty wild ideas about how to define the good life for those who follow Him.

Jesus managed to pack a lot of His world-upending truth into the Sermon on the Mount. For my money, though, it’s His preamble, the Beatitudes, that really turns you inside out. On the surface, it’s all blessing and reward, and so it can be easy to gloss over. But wait until the end. Jesus’ big finish is, more or less, People are going to hate you. And slander you. And hurt you because you associate with Me. That’s a good thing. Living out the Beatitudes, in other words, does not appear to end well. There is very little we’d think of as comfy in the preamble, much less the Sermon on the Mount. But that’s the point.

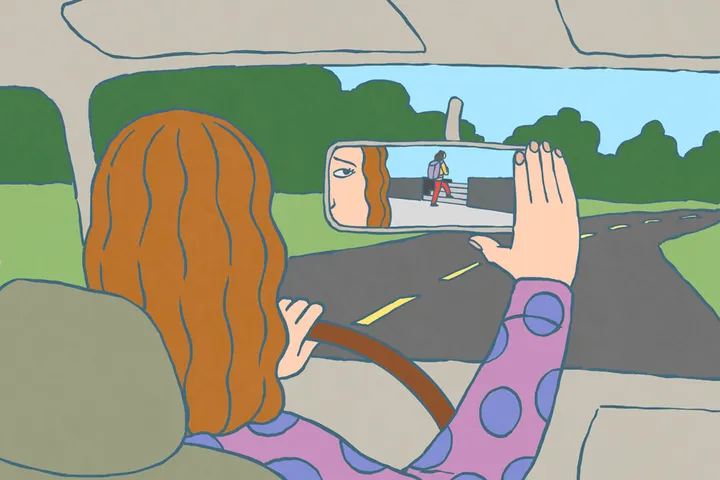

This brief poem of Jesus’—and indeed the entire sermon that follows—is all about retraining our affections. Learning to love new things deeply enough to realize some of our old affections are very much unlovely. In essence, you can read the Beatitudes as an outline of a rather invasive “surgery.” A kind of spiritual heart transplant, really.

In the somewhat meandering career path I’ve found myself on, one of the less expected and more eye-opening jobs I had was working for a medical subcontractor as an “endoscopic surgical technician,” which may sound fancy, but really I was just a bystander in the operating room. The job consisted of me hauling a video tower along with a tackle box of surgical tools into the hospital OR, plugging the camera into the machine, and watching the surgery on the little TV while all the real hospital employees pretended I wasn’t there. And, lest this somehow sounds more glamorous than it was, I saw two surgeries on repeat: gallbladder removals and gastric banding.

Living out the Beatitudes does not appear to end well. There is very little we’d think of as comfy in the preamble, much less the Sermon on the Mount.

What I learned is that a gallbladder doesn’t do much, and definitely nothing essential to life (hence being able to remove one). But still, the surgeons had to take care so that bad outcomes wouldn’t happen–things like infections, abscesses, and internal bleeding. Though it had to be rote to them, each surgeon was always careful and efficient. They would find all of the various connections and support structures that held the gallbladder in place and kept it alive, then sealed them off so the organ could be extricated. Seeing the intricacy of a procedure that merely removed a small non-vital organ, I can only imagine the delicacy of a transplant procedure where 1) what you just took out very much needs to be there and so 2) you’re putting something back in its place and reconnecting all the things you just severed. It’s miraculous.

In the Beatitudes, Jesus is aiming for not mere comfort but the miraculous: removing a heart of stone and replacing it with a heart of flesh, in the words of Ezekiel 11:19. It’s with this image of cutting away in mind that Jesus’ not-so-blessed-sounding blessings begin to make sense. With each beatitude, He’s isolating something we think gives us life and tying it off in order to cut the old heart free:

He says, “Blessed are the poor in spirit,” as He clamps off the blood supply of myriad frail and fleeting things we think make us rich.

In the Beatitudes, Jesus is aiming for not mere comfort but the miraculous: removing a heart of stone and replacing it with a heart of flesh.

With “Blessed are those who mourn,” He turns His scalpel to the outflow of our heart, which we think must always seem happy so that people will accept us.

With “Blessed are the gentle,” He sews up our anxious drive to climb and clamber to the top of the heap.

When Jesus says, “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness,” He connects the new blood supply.

When He tells us, “Blessed are the merciful,” our new heart beats with the ability to forgive.

And with “Blessed are the pure in heart … blessed are the peacemakers,” the transplant is complete, and our relationship to God and neighbor are both reconnected.

The arc of Jesus’ heart procedure starts in a valley of sorrow and poverty, moves to the cutting off of the old life, and passes into a place of peace. But it still ends with the specter of persecution. Rejection is the shadow that haunts the Christian life. So why do we submit to such a strange “surgery”?

We come to Jesus when we come to the end of ourselves, after we have spent far too long, perhaps, clambering for attention or acclaim, holding grudges, chasing riches, not loving our neighbors, not truly loving ourselves but instead making the self into an idol. Then one day, in His mercy, God allows us to feel how sick at heart we are—which is usually a pretty bad day. But then there’s grace. There’s Jesus on the cross, taking all of that sickness and all of the death upon Himself. He takes it into the grave and comes back without it.

When we see these two things clearly—our sickness and our Savior—we become so absorbed in the miracle of Christ’s resurrection that we grow in our ability to trust Him implicitly. When He says, “Let’s do something about that heart,” we trust Him. We trust Him though it hurts. We trust Him though it makes us appear foolish. Then the longer we trust Him and the longer our new heart beats, the stranger our old obsessions seem to us. Paltry, fading things, one day to be forgotten entirely.

You go in for surgery when you’re sick and nothing else is working. It’s not so much that pain and social ostracism begin to feel good. No, hurt is still hurt. I think it’s more the case that with a new heart, what we love and what we forget radically change. Switch places, even. We used to obsess over our own life to the point that we forgot about our Creator and Father and spurned our neighbors. A lonely state of affairs, mind you, that creates much more pain, not less. But now we are so absorbed in the miracle of Christ’s resurrection that pain and social outsiderness are overshadowed by a deep sense of peace and belonging with God and with God’s people. The reward of our new, pure heart is the thing our heart desires most and what it was made to enjoy above all else—seeing God in our midst.

Illustration by Adam Cruft