I do not go to sleep easily. When I do sleep, I often do so lightly. I wake in the middle of the night, disturbed by the creaking house as it shifts on its foundation, or startled by the bushes rustling outside my window. My wife’s breathing beside me is quiet, rhythmic as an incoming tide. But in the distance, I hear the shriek of an ambulance, and I wonder whose misfortune it laments. I replay the events of the day in my mind, reviewing its conversations and improving my contribution with imagined wit. I brood over the past. I fret about the future. The clock on the nightstand counts down the remaining hours, and I lie in the dark, waiting for the window to brighten with the gray light of dawn. I am not the only one lying awake in the dark. According to the National Sleep Foundation, more than half of all Americans say they have problems sleeping at night. We are a sleep-deprived culture.

The church suffers from a similar problem. Not from sleep deprivation so much as a deficit of rest. Today’s congregation is a frenetic place. Our worship is marked by frenzied devotion that has full congregational participation as its primary goal. The drummer marks the tempo for the first song, and we rise to sing. We remain standing through the entire song portion of the service. We are urged to lift our hands or clap in an approach to worship that sees it as a full-body experience.[1] Between songs, the worship leader tells us to fan out and find someone to whom we can introduce ourselves. The pastor reminds us to stop by the information desk and sign up for the latest congregational project and then spend time chatting over coffee with someone in the vestibule.

In other churches, the start of worship is still signaled by the reedy call of the organ. Although there are no drums here, there is just as much activity. In this case, the pressure is focused on church attendance and involvement in its programs. Those who love Jesus should be present whenever the church doors are open. To be about Christ’s business means to attend to the church’s business. Members are urged to serve on committees, teach Sunday school, and listen to children say verses on Wednesday night. At least some—about 20%—do. Others feel ill at ease, trying not to look the pastor in the eye as he issues the latest appeal for more help in the nursery.

Today’s highly driven church constantly strives to exceed its current level of activity. If attendance has grown, it should increase further. If programs have expanded, they must expand even more. Every year the church rolls out new initiatives the way automobile companies roll out new products. Like the latest-model car, the church’s new project needs to be more impressive than the last. But when church members are put under this kind of pressure to produce, the community of believers loses sight of itself as a kingdom of priests, picturing instead a service industry whose primary mission is to provide spiritual goods and observances to the masses. They treat visitors like consumers and members like employees whose main job is to promote the brand. The implied message is that, for the congregation, it’s not enough simply to come to church and worship. We must bring something else to the table. We must add value. We must produce.

Steeped as we are in such a culture, it is startling to hear the different note in Jesus’ invitation. In Matthew 11:28-30, He says, “Come to Me, all who are weary and heavy-laden, and I will give you rest. Take My yoke upon you and learn from Me, for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For My yoke is easy and My burden is light.” In the same way, Jesus’ picture of the blessed life described in the Beatitudes does not focus on the value we add to the kingdom or on how well we perform for the church, but on what we lack. What Jesus says in the Beatitudes is unexpected. What kind of blessing can come from knowing what we are not? As someone once said, “Nobody is helped by negatives, even when they are true.”

However, the Beatitudes are not a performance review or even a target to aim for. They are a reality check. When we read them, we know intuitively where all the checkmarks will fall. They will land in the box that says “needs improvement.” The Beatitudes are a diagnosis that also reveals the fundamental flaw in the church’s productivity mindset. Those who look to their own reserves to calculate whether they have enough holiness to find acceptance with God will inevitably come up short. If you want righteousness, you cannot seize it by force. As Jesus Himself said, it is only the sick who need a doctor (Matthew 9:12). This is what the Bible calls grace, and where grace is concerned, only empty is enough.

We are skeptical of such a message. Not only because of the performance-oriented culture of today’s church but because of our nature. Our natural way of thinking is antithetical to the gospel. As philosopher Josef Pieper put it, “Man seems to mistrust everything that is effortless; he can only enjoy, with a good conscience, what he has acquired with toil and trouble; he refuses to have anything as a gift.” What the church needs is rest. But it’s a special kind—not merely the stuff of days off and vacations but something only Christ can provide. It’s both a remedy and a relief, and He offers it as a gift. It is also the key to the kind of blessedness that Jesus describes in the Beatitudes. These blessings are not payments for services rendered but Christ’s gracious provision for those who lack. As Martin Luther said, “Before you take Christ as an example, you accept and recognize him as a gift, as a present God has given you and that is your own.”

Luther’s observation is also the answer to the question I am frequently asked when it comes to rest: “How exactly does one go about it?” When I answer, I’m not speaking of a life that can be lived by only a select few. Christ’s invitation in Matthew 11:28-29 is addressed to all who labor and are heavy-laden. But in a world made up of workers, rest itself is a radical notion. And in a church that believes worshippers must also be workers to justify their presence, it’s an uncommon experience. While there are some disciplines, like sabbath, solitude, and silence, that can help us restructure our lives and reorient our thinking, rest is not primarily a matter of methodology. We are so performance-oriented that we are liable to turn the experience into yet another task. We add the disciplines of rest to our list of things that we must do for Jesus and miss the point altogether. As one person said to me, “All this talk about rest just makes me tired!”

At the same time, even though rest is not a matter of methodology or a particular discipline, it is something that must be pursued. The Bible describes it as both a gift and a destination. That’s why the writer of Hebrews urges us to “make every effort” to enter that rest (Hebrews 4:11 NIV).

This holy pursuit also does not relieve us of the obligation to serve Christ. Indeed, our service depends upon what Christ alone can provide: We don’t serve our way into rest, but the other way around. We serve out of rest. And it is Christ’s cross that enables us to take up our own. This yoke[2] of rest Jesus offers can be received, but it cannot be seized by force, acquired by bargain, or even attained by discipline.

On the surface, rest might sound like something that exists apart from Christ—as if Jesus were a parent giving a coin to a small child. But Jesus is the subject of the verb in Matthew 11:28, and we are the object.[3] What Jesus says might be translated roughly as “I will rest you” or “I will refresh you”—a promise that is as relational as it is experiential. We come to Christ, and He refreshes us. We do not come to Christ, receive His gift, and then go our way. By offering us rest, Christ offers Himself. And this is what we so often fail to see: Rest is synonymous with the Son of God, who is both its primary proponent and chief architect. The first step is also the last step: Seek Jesus. Because if rest is a destination, I must be carried in order to reach it.

Somehow those of us who once embraced the gospel of grace have come to believe that the maintenance of the Christian life depends solely on us. We have been persuaded that our value in God’s sight is linked to what we accomplish on His behalf. As a result, we have been beaten down by our own ambitions, even though they are spiritual ambitions. But there is more to the Christian life than working for the church.

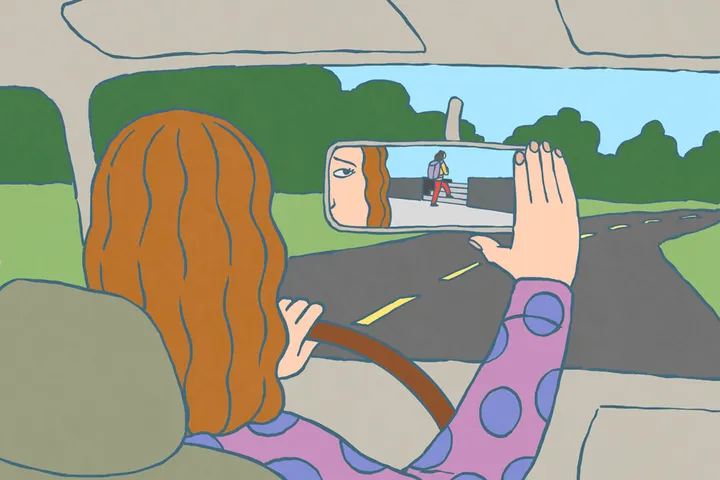

I do not go to sleep easily. Yet if I wait long enough, sleep eventually comes to claim me, always as a surprise, greeting me like a lover who sneaks up behind me and covers my eyes. So it is with Christ. When we find Him, we enter into rest—the very thing He intended from the beginning. As Augustine confessed, God made us for Himself. And we will always be restless until we rest in Him.

Illustrations by Mark Wang

-

Throughout the Bible, worship involving all the senses has been part of the way God forms relationships with those who believe in Him. This is seen in things like the use of incense in the Old Testament and Thomas’s need to touch Jesus before believing. Even today, we engage our senses when we worship in private or in the presence of others—by listening to songs and hymns, praying aloud, shaking hands with people in church, and tasting the bread and wine (or grape juice, depending on your congregation) when receiving Communion.

When Paul wrote about “true and proper worship,” he encouraged offering our bodies as a living sacrifice (Romans 12:1 NIV). Worship is a holistic, full-body experience that affects every aspect of our life—it is expressed not only through songs and hymns but also in stillness and prayer, service and hospitality. If this feels different than the message proclaimed by the world, it’s because the Christian experience is a countercultural one—the world promotes focusing on self, whereas we look to Christ and hope in Him.

-

When we look beyond Christ’s metaphor to the practical use of the yoke, we see its initial purpose was to align two animals in the same direction. Only when oxen are parallel can the yoke bows (the loops that wrap around the animals’ necks) push through the holes of the beam, securing the pair in a position that enables them to move a load together. It’s no wonder, then, that zygos, the Greek word for “yoke,” also gave us the word syzygy. This astronomical term refers to the alignment of celestial bodies, such as those that create a solar or lunar eclipse.

-

A sentence is commonly defined as a textual unit that expresses a complete thought. To create one, there are only two basic requirements: a subject and a verb. The subject can be either a noun or pronoun, and the verb can be active (run, jump, dance) or linking (is, am, was). Additional information may be added by direct objects (the result of an action), indirect objects (things that receive or respond to the outcome of an action), or objects of the preposition (nouns or pronouns that modify the meaning of a verb). Christ, like the subject, is the only necessary actor, His will the verb. Much like the object of a sentence, we can only receive the result.