In high school, my dream was to become a Christian apologist: ultimate defender of the faith. I attended a conference where, during the final Q&A session, a man approached the mic and asked, “How should we as Christians respond to our nation’s most recent election?” He lamented that the new president claimed to be a Christian and yet promoted political policies that seemed antithetical to the faith. In response, one of the panel speakers shared his experience as a Christian in India. There, he said, they lack the luxury of choosing the “more Christian” candidate and simply elect the lesser of evils. Not only is their Hindu government hostile toward local churches, but its corrupt systems also affect every area of society, oppressing citizens daily.

A man approached the mic and asked, “How should we as Christians respond to our nation’s most recent election?”

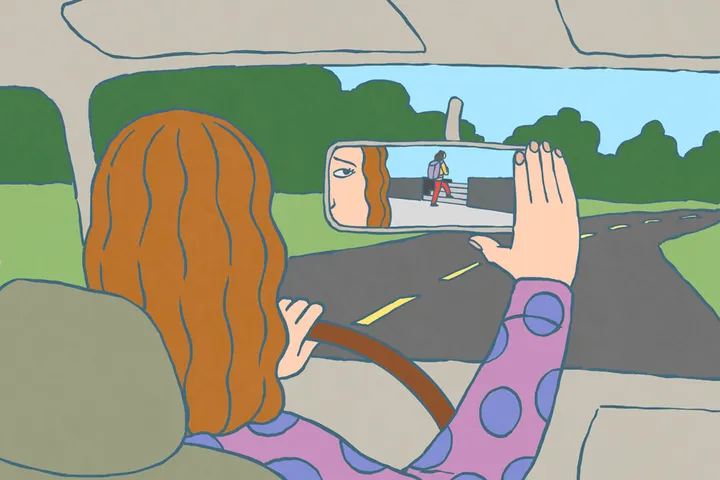

Back then, when I considered the man’s question about how Christians should respond, I thought the solution was merely better public relations. My goal as an apologist would have been to restore the reputation of Christianity so the faith could once again be at the center of culture, shaping every part of it. But now I see how much I misunderstood the kingdom of God.

At the time, I believed the best way for us as Christians to impact the nation was to exercise our civic duties and leverage our rights as citizens. And while we shouldn’t neglect these, I have since paused to consider the nature of our primary citizenship: For us as citizens of heaven living on earth, where does our ultimate hope lie?

Years after that conference, I traveled to India. I was staying in the part of Delhi filled with tourists, where the government hired workers to clean the streets daily, trim all the greenery, and sweep around the monuments. But when we visited a small church on the city’s outskirts, the scene changed drastically. As we approached the building, the smell of a nearby canal filled my nostrils, and I noticed an empty lot next door, which over time had become an unofficial dump, collecting about three feet of refuse. To me, the neighborhood seemed unlivable—marred, as it was, by unmistakable poverty. I wondered what a local church planted here looked like. Weren’t they overwhelmed by the needs around them?

These believers have learned not to put their faith in the government.

When I finally met the faithful gathered here, I saw no trace of despair. I’ll never forget the crowd who came forward for prayer after the service. It seemed the entire congregation had gathered at the altar—for everything from physical sickness to unbelieving husbands. Even families from the street began pouring into the room. And as these men and women prayed for their brothers and sisters in Christ, I could tell their faith was as fervent as the needs before them were palpable. I realized that these believers, much like many others in developing countries around the world, have learned not to put their faith in the government. Instead, local churches operating in areas of great need have been forced to rely upon the sovereign power and provision of God.

A while later, in Israel, I found a different situation in which the government overtly allows religious freedom—and yet seeks to preserve the nation’s Jewish identity. They do so by making it difficult for Christian communities, both Arab and Messianic, to establish and expand. One church we visited met in a small, unmarked building, down a narrow gravel alley we mistakenly passed several times. As I interviewed the pastor in his office, he showed me the miniature model of their newly built facilities, which looked far more like the churches I grew up attending. He told me it’s taken them nearly 20 years to follow the proper procedure. The government “lost” their documents several times, he said, and even now, they are still waiting on the final occupancy permit.

The pastor led us into their current sanctuary—a nondescript tiled space the size of a large living room—and said that most of the 200 members sit in the alley. As I pictured rows of families seated outside in plastic chairs, listening to the service through speakers, I couldn’t help but wonder, Would this happen where I lived? Almost certainly not. Back at home, people leave churches over the use of drums or the inclusion of chairs instead of pews. I couldn’t imagine people staying in a church without air-conditioning or a roof over their heads.

While reporting in Cuba in 2017, I interviewed a group of local pastors, who told me about the house church movement and how it has flourished, even in times of great persecution. But I was surprised when one of them—a man with gray hair and sun-leathered skin—seemed concerned about his nation’s growing religious freedom. I expected him to express a sense of relief, or maybe even triumph. Instead, he said he was worried this would cause believers to grow complacent. After all, he’d witnessed fervent passion in previous decades, when being a Christian had a high cost. It struck me that this Cuban pastor wasn’t interested in making the world look more like the church, but in preventing the church from blending in with the world. He didn’t lament that Christians were marginalized in their society or government. Instead, he seemed to consider this their greatest source of influence. To him, their local church was a city on a hill in the midst of a fallen nation. After all, how can light shine if there is no darkness?

In 2018 I went to Greece, where I saw an evangelical community who accepted their place as a small minority with no political power—but whose impact was indisputable. Years before the Syrian refugee crisis, the country’s economy had crashed, leaving thousands out of work and homeless. With so many of their own citizens in need, believers could easily have resented the massive influx of refugees, but they never had a choice. Families began arriving at their coastline on rafts, and so they mobilized, regardless of denomination—making meals, bringing blankets, spending midnight shifts on rocky beaches in freezing rain to receive the incoming refugees. This, I realized, was the church’s hidden power made manifest. When the world has too many problems of its own to provide hope for those most in need of it, the body of Christ stands ready like a lighthouse on the shore, welcoming the weak and the weary.

My experiences abroad make me consider why local churches in places like these are not just surviving, but thriving. In reflecting, I see a pattern emerge. Where Christians are a marginalized minority in their society, one can see greater unity in the Spirit and dependence on God. The weaker their worldly influence, the stronger they seem to be in their faith. Maybe it’s only when we recognize the insufficiency of our human systems that we acknowledge our great need for ways and thoughts higher than our own. When we stop clinging so tightly to earthly kingdoms, perhaps we too will cast ourselves upon the grace and power of God.

Illustration by João Fazenda