His face pops up on my Facebook timeline every so often, and when it does, it makes me sad. In high school we spent so much time together. We both played on our basketball team. I dated his sister. And for a couple of years I spent every spare moment riding around in his sleek black convertible.

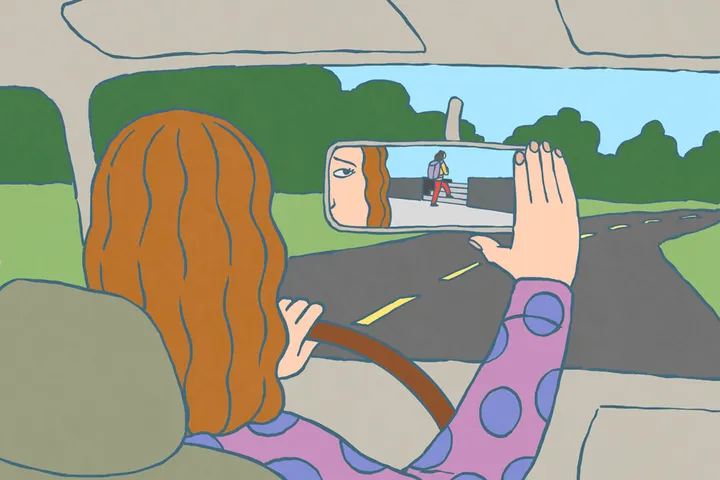

Brad was always adventurous, curious, and kind. But our paths diverged. I continued on, struggling as we all do, with Christ. He, not so much. From his Facebook posts, I gather that he’s still doing what he was always tempted to do: move from relationship to relationship, idea to idea, always testing the boundaries. When I was younger, I used to think his life looked so much better than mine. Though I didn’t often stray (at least in public ways), I wondered how it would feel to try Brad’s wild, seemingly limitless life. Like the older brother in Luke 15, who worked as his sibling squandered an inheritance, I’ve often gazed, with curiosity, at the audacious ramblings of prodigals. And have asked myself, Is Brad’s way possibly more fun? More creative? More human?

Is the way of prodigals possibly more fun? More creative? More human?

But Facebook, that great digital class reunion, has a way of reminding us that rebellion against God is not the wild and creative life we envision it to be when we embark, as Jonah did, on ships to faraway lands. Rebellion, ultimately, is more boring than the surrendered life in Christ. Because sin is ultimately a failure of imagination. Of course, Facebook is closely curated, but even this carefully managed life of my friend—parties, different girls on his arm, and a carefree attitude—reveal a kind of emptiness. Brad is still living that life? I often muse with sadness.

To Be Human

Brad is not doing anything unusual, really. He’s simply following the cultural ethos of “be true to yourself.” This is, in essence, how Satan seduced Adam and Eve in the garden. It was the offer of a more full human experience. Your obedience to God is keeping you from what you can fully be, the serpent suggested. Ironically, however, to follow the enemy into sin was not to experience a fuller humanity, but a diminished one. Created to rule over animal life, Adam was now subjecting himself to a snake. Sin is a subhuman act, a willing relinquishment of our God-given dignity.

When we mess up, the phrase “only human” is thrown around as an excuse. And of course that’s true in a sense; we are acknowledging the corrupted nature of the human condition. Our sin shouldn’t surprise us, nor should we be taken aback when others sin against us. But sin is not natural. It’s not human. Nor is it the way we were designed by God to live in His world.

We can see this just by observing the brokenness around us. Violence against other image bearers is an animalistic behavior that strips both the victim and the perpetrator of their dignity. Sexual sin creates an illusion of soulless, conscience-free pleasure. Racism wounds minorities but also eats away at the soul of the bigot, making him unable to love and feel.

It is ironic that in trying to be like God, by believing the lie that we are more than our humanness, we become less. Instead of fully realizing our image-bearing purposes—to create, worship, and love—we end up enslaved to our desires.

A Failure of Imagination

Thankfully, God—in Christ—seeks to rescue us from ourselves. He both exemplified what it really means to be human and rescued us from the sin that subverts our humanity. Faith, then, means we believe that our lusts are poor masters and the existence God imagines for us is infinitely more glorious than the paper dreams we hold in our hands.

We always aim for something lower than that for which we’re destined.

This is essentially the story of God’s interaction with His people throughout history. We always aim for something lower than that for which we’re destined. Abraham envisioned a son who could continue the family of Israel. God, however, envisioned a people whose members would outnumber the stars in the sky. Abraham wanted to build legacy for the next generation. God was calling out a people for His name, first in Israel and then in Christ—a people from every nation, tribe, and tongue.

King David had big dreams for himself. He spent sleepless nights imagining a beautiful temple for God in Israel. (See Psalms 132:4-5.) This was a noble dream. He desired to see God receive greater attention than the false gods of other nations. However, God had even more imaginative and creative dreams than David could envision. God would not simply see a temple built in Israel, but would establish an everlasting kingdom from David’s family.

The apostles desired a king who would rescue them from Rome and finally establish God’s kingdom on earth. Jesus envisioned not only the rescue of His people from their sin but also the final eternal kingdom that would stretch far beyond the borders of Israel—a kingdom where mercy and justice reign and where the righteous rule in peace forever.

Most of us understand that the Christian life calls us to die to our dreams, to deny ourselves and take up our crosses. We understand that to follow Christ is to follow Him into suffering.

Jesus calls us to die to our dreams, not because our dreams are too big, but because they are too small.

But what we miss is that Jesus calls us to die to our dreams, not because our dreams are too big, but because they are too small. We should lay aside our plans, not because they are too detailed, but because they are not detailed enough. We have five- and 10-year plans, but Jesus has trillion-year plans for us. What we give up in this earthly life, we make up for in the reality of the new heavens and new earth. For that reason, we can relinquish power and titles and wealth here because those things are worthless relics compared to the power of ruling with Christ in His kingdom and the blessings of the New Jerusalem. The prosperity gospel, it turns out, fails because it is too shortsighted, too pedestrian, too unimaginative.

Redirected Dreams

This is why the gospel is good news for dreamers and visionaries and creators. As God’s image bearers, we were uniquely created to create. It only when our creative acts turn from worship of God to worship of self that things go awry. In that moment, our hands turn to violence, our hearts turn to lust, and our longing to rule turns into a craving for power. The gospel, however, restores us to the original purpose for which we were created. Jesus, by crushing the serpent, redirects our gaze back to our Creator.

So as Christians still tempted to sin in a broken world, still groaning in anticipation of Jesus’ return, we should look at every temptation and see it for what it really is: an invitation to bondage, not a burst of freedom. Disobedience is not a brave act, but a relinquishing of our true humanity.

This is why I wish I could go back and tell my teenage self that the luster of indulging corrupted fantasies will fade, the glow of having it our way turns dim, and the loneliness of pleasing self, in the end, is what robs us of true joy. In other words, I wish I knew then what I know now: Certain choices are destructive, but the way of Christ, while often winding and hard, is so much better.

Illustration by MUTI