A few months back my daughter dislocated her shoulder. At the time, it was a real mystery to us. Dorothy doesn’t recall doing anything in particular to cause the shoulder to pop out of joint; she just realized, during school, that she couldn’t raise her arm.

We found ourselves in an emergency room, talking to doctors about what might be wrong. Some kids, they said, have lax joints and this sort of thing just happens. There could have been other underlying causes, too—joint disorders or autoimmune diseases. As we sat there, a world of possibilities opened up. An injured shoulder could mean any number of scary things. More immediately, it would mean putting my daughter under general anesthesia and resetting the shoulder.

When the time came for the procedure, we moved into something akin to a large operating room. They dressed Dorothy in a hospital gown, laid her on a gurney that was way too big for her, and put an IV into her small arm. They explained the procedure and then told us to go sit nearby. “Don’t worry,” they said. “We do this all the time.” What seemed like an army of doctors and nurses lined up around her. The doctor who was taking the lead told Dorothy to start counting backwards, and they injected the anesthetic into her IV. She was quickly asleep, and the medical team jumped into action, manipulating her arm and trying to move it back into place.

Two things immediately went wrong. The first, we saw, was a sense of panic from the doctors because the joint wasn’t cooperating. The second was when an alarm sounded. The anesthetic had stopped Dorothy’s breathing.

We stared wide-eyed as they bagged her and pumped air into her lungs. Miraculously (and I really mean it when I use that word), a young doctor wandered into the room and asked what was going on. It turned out that he was a pediatric orthopedic resident, and on seeing the trouble with her joint, he quickly took over. At the same time, she started breathing normally again, and they stopped the flow of the anesthetic. The room stopped spinning. One by one, nurses and doctors left, assuring us everything was fine. And in fact, it was. Dorothy soon woke up and sipped at a Sprite. Our pulses returned to normal. We took her home and put her to bed.

My wife and I closed her door, looked at each other, and began to weep.

When you’re afraid, your body goes into action, and the fight-or-flight response kicks in. Additional blood flows into your muscles, which can make you feel jittery and edgy. You sweat or get goosebumps. These reactions are nearly universal, and part of the human experience from the time of birth. It is inescapable that you will experience fear in your life; the question to ask is how to deal with it.

In the aftermath of my daughter’s injury, our desire to protect her was strong. We wanted to find a way to lock her shoulder in place. To be sure she never had to undergo anesthesia again. In the days after her injury, if you had offered us a protective shell to put her and her sister in, we’d gladly have taken it. But something remarkable happened when we took her to an orthopedic surgeon. He more or less shrugged his shoulders and encouraged us to lighten up. “This is just her,” he said. “This is her challenge, and she can live with it.” We asked about future implications for sports and play, and he again shrugged his shoulders. “Once she’s done with physical therapy, she can do whatever she wants. She might grow out of this, or she could dislocate it again. But we can find ways to cope.”

Physical therapy became an important part of life for the next several months. Each week, the therapist would challenge Dorothy to use the shoulder more, doing a variety of exercises that brought strength and stability to the joint. The way to keep the shoulder healthy was to use it, to confront it, to challenge it head-on—not to restrain it in the name of protecting it. To me, this seemed counterintuitive.

Fear is inescapable, but our reactions to it can lead us in many directions. Sometimes our most immediate instincts—in this case, to withdraw and protect—are the exact wrong ones. What if the biblical witness calls us to courage and confrontation? It seems counterintuitive, but it’s exactly what we find when we begin to look around.

The phrase “fear not” appears dozens of times in the Bible. God says it. Angels say it. Jesus says it. It’s a persistent theme, to be sure. However, if we’re not careful, we might misread it as a moralizing statement about fear, as though the feeling/emotion itself were sinful or wrong. Instead, we should see these statements in the context of the stories they occupy. “Fear not” is the response to fear, not a shaming of it. It’s an invitation to courage—to draw near to the presence of God or go into the world with the confidence that God is with us.

An extended passage about fear is found in Isaiah 41. It climaxes with verse 10, where the prophet writes, “Do not fear, for I am with you.” The context of this scripture is so helpful for understanding why God invites us to “fear not”—the two verses immediately preceding it read, “But you, Israel, My servant, Jacob whom I have chosen, descendant of Abraham My friend, you whom I have taken from the ends of the earth, and called from its remotest parts and said to you, ‘You are My servant, I have chosen you and not rejected you’” (Isaiah 41:8-9).

Before God tells us “do not fear,” He reminds us of who He is and what He has done. He’s Abraham’s friend who has “taken” us, “called” us, and “chosen” us. This reality lies in the background of our fearlessness: We belong to God, who loves us and calls us friends. He’s brought each of us to a place where we can know Him, and as His children, we’ve been rescued from the very worst thing that could ever happen—separation from Him. We’re drawn in, and that gives us reason not to be afraid.

Then we come to Isaiah 41:10: “Do not fear, for I am with you; do not anxiously look about you, for I am your God. I will strengthen you, surely I will help you, surely I will uphold you with My righteous right hand.” The Lord is “with” us. He will “strengthen,” “help,” and “uphold” us. The God who calls us His own will not abandon us. These aren’t platitudes, especially for Isaiah’s original readers, who were surrounded by hostile nations. The passage goes on to say, “Behold, all those who are angered at you will be shamed and dishonored; those who contend with you will be as nothing and will perish. You will seek those who quarrel with you, but will not find them, those who war with you will be as nothing and non-existent. For I am the Lord your God, who upholds your right hand, who says to you, ‘Do not fear, I will help you’” (Isaiah 41:11-13).

Because He is our God, the threats that surround us can ultimately do us no real harm. For Israel, this promise was political. In the new reality Jesus inaugurates, these promises still hold, but in a much deeper way. We know that our enemy isn’t flesh and blood. The real enemies—those who are “angered” against us—are Satan, sin, and death. They will become “as nothing.” The kingdom of God is advancing in a way that ultimately will result in their end.

Consider, then, how that transforms the way we see our world—our “enemies,” our conflicts, and even our understanding of danger. Jesus Himself tells us, “Don’t fear those who kill the body but are unable to kill the soul” (Matthew 10:28). These were hard words for Jews oppressed by Romans and hated by their Samaritan neighbors. And yet Jesus tells them not to fear what such adversaries might do to them but instead to “fear Him who is able to destroy both soul and body in hell. Are not two sparrows sold for a cent? And yet not one of them will fall to the ground apart from your Father. But the very hairs of your head are all numbered. So do not fear; you are more valuable than many sparrows” (Matthew 10:28-31).

These should be hard words for any reader, and they are certainly challenging for us. In North America, we’re surrounded by a culture that preys on fear. It fills the rhetoric of our politics. It fuels our consumerism. It makes space for a kind of pervasive, simmering anxiety. Psychologists talk about fear as one of our “primary emotions”—an emotion that often lies underneath other emotions like anxiety and anger. Yoda spoke of this, too, when he warned Anakin Skywalker that “fear leads to anger. Anger leads to hate. Hate leads to suffering.” Yes, wise words spoken by a green puppet, but true nonetheless.

When I think about anger as a secondary emotion, I can’t help but think of the awful images from Charlottesville: white supremacists marching with torches, their faces filled with rage. Surely behind this anger is a much deeper fear—fear of loss, fear of inadequacy, and most of all, fear of the “other.” The response to such anger, from those who understand it, should be pity, prayer, and hope that at some point they can hear a prophetic “fear not” and repent.

What might it look like for the church to be a place of righteous fearlessness? For our communities to be marked by a countercultural spirit of confidence and courage, fueled by the knowledge that we belong to God and nothing can truly hurt us once our souls are secure in Him? What if we were a consistent, prophetic voice saying, “Fear not”? The world might be a place of greater peace. It would certainly be a place with less anger.

This isn’t to say there aren’t dangers and pressures we must face. The church is in a tenuous place in our culture, as secularism is on the rise and religious liberty is contested. But instead of letting fear drive us into the mountains or into hidden enclaves of private faith, we should follow Jesus’ invitation from that passage in Matthew: “What I tell you in the darkness, speak in the light; and what you hear whispered in your ear, proclaim upon the housetops” (Matthew 10:27). In other words, be boldly present to a hostile world, and make the kingdom of God visible where it is invisible. Invite the world to know the God who tells them, “Fear not.”

Likewise, a countercultural fearlessness will make us suspicious of those who stoke anxiety and rage. When politicians, pundits, and other talking heads tell us to be afraid—whether they’re fueling fear about what a party might do, what cultural changes might be taking place, or what the “others” in our world might be capable of—we should resist them. We can take seriously the call to care for the widows, orphans, sojourners (read: immigrants), the poor, the sick, the elderly, the angry, the broken, and the lost and draw near to them in spite of whatever fears might arise. We trust our lives to God’s care and move toward the world, not away from it.

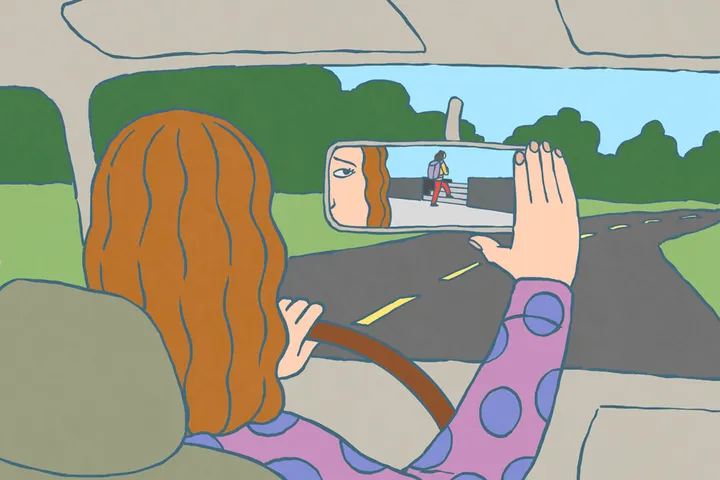

Collage by Eddie Guy