Raising adopted children can sometimes feel like walking across a minefield. The sun may be shining and the grass verdant, but beneath the surface there are hazards beyond number. Seemingly mundane things—a certain brand of candy, a familiar place, a song on the radio—can trigger memories in our boys, and these recollections must be safely “detonated” through conversation and active listening. There is no skirting these dangerous places; the hurt only grows worse through avoidance. As parents, we have the sacred task of helping them process their loss and come to terms with what they suffered at the hands of those previously charged with their care, people they love and miss despite many grievous failures.

Every story has to have a villain, and in the tale I was weaving, the boys’ birth mom fit the role perfectly.

We knew a challenge like this was coming weeks before they moved in, the first time we read their adoption dossier, in fact. It was, to say the least, spiritually and emotionally taxing. Dossiers contain the notes of every case manager who has overseen a child’s care (often several individuals, since burnout is common and turnover high). They include a family history as well as reports and evaluations by law enforcement officials and medical experts. All the details are filed away in tidy columns and checklists, and the clinical nature of such documents has a way of sanitizing things, making it easy to overlook phrases like “suspected drug abuse” and “chronic homelessness.” But each phrase is explosive, and the shock waves continue to ripple outwards—even into the lives of people who become a part of their story after the fact. That is certainly true for me.

Our sons’ dossier is ripped and crinkled in various places where I read something that compelled my hands into fists. I’ve read certain sentences aloud, hoping for some reason that they would become less awful in the hearing. They rarely did. And the dismay didn’t fade after multiple readings, either. I even highlighted passages, transforming them into kaleidoscopic scars on the page, and the marker in my hand became as malicious and dangerous as a Pharisee’s stone. (See John 8:1-11.)

Every story has to have an antagonist—a villain, the person on whom blame rests—and in the tale I was weaving, the boys’ birth mom fit the role perfectly. What kind of woman could neglect her child’s medical needs like this? I would ask myself. Who could continue making such awful choices, knowing she was hurting her kids? Over the next few months, my anger crystallized into a spear, and I aimed it directly at her heart, this woman I did not know.

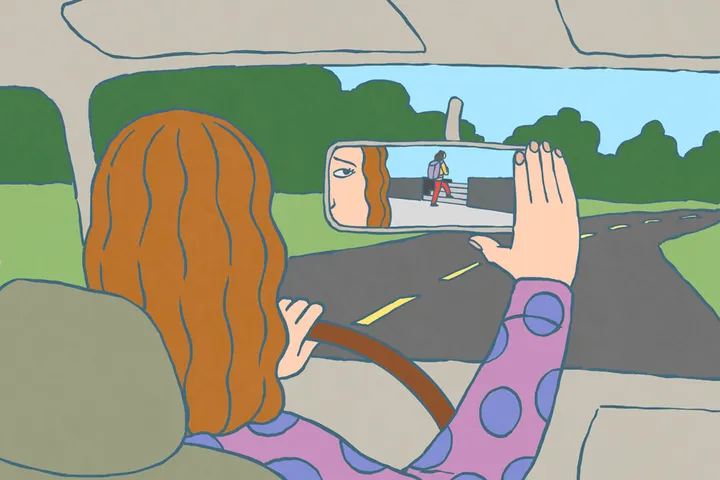

When the boys arrived, they came with a colorful assortment of challenges and developmental delays, some of which were unavoidable challenges of biology. But far more were caused by poor medical care, sporadic school attendance, and a lack of safety and structure. The sheer amount of work before us was staggering, and though I’m not proud to admit it, my anger turned to wrath. I wanted to ride into the story like an Amazon warrior from Themyscira, decked out in gleaming armor, sword drawn and eyes blazing. This kind of failure, this sin, required justice, and I was more than willing to dole it out. Christ’s admonition—“Do not judge so that you will not be judged. For in the way you judge, you will be judged; and by your standard of measure, it will be measured to you” (Matthew 7:1-2)—was nowhere on my self-righteous radar.

And then came “The Day.”

My older child’s left hearing aid was broken, and I had no idea where to get it fixed. My younger son had had a particularly rough day at school, causing the principal to call me in for a conference. Our case manager had dropped in for a visit and stayed so long waiting for me to fill out the paperwork I’d forgotten that I was late getting dinner on the table. We were all tired, hungry, and at the end of our rope. In one day, the well-oiled machine that was our life exploded, sending parts flying in all directions and filling the house with smoke.

I lost it. I screamed, slammed things, railed, and shut myself away in a closet to sob.

Even with all the resources I have—an education, employment, reliable transportation, a house in a good neighborhood, food on the table, medical insurance, friends to lend a hand—it is still challenging to care for our boys. How had she managed it for a few months, let alone years? I wondered, wiping my nose with a shirtsleeve. Sure, my family had been poor when I was growing up, but I’d had a mother and father who loved one another, a stable home life, and a safety net.

When my husband and I were first married and struggling to make ends meet, my grandmother told me, “Baby, we won’t let you get in a mess. If I have to scrape the bottom of the barrel, I’ll split it with you.” It had always been that way. When trouble came knocking, my family went to the front door to answer it together. That kind of certitude has a way of shaping a person. It undoubtedly gave me a different perspective and helped me to make decisions with the long game in mind. My boys’ birth mother had few or none of those advantages. Sure, she’d made poor choices—I’m not trying to excuse her by any means—but ignorance and desperation, rather than malice, accounted for many of them.

I was holding my sons’ birth mother accountable for not making the choices I’d been taught were right.

In the opening lines of The Great Gatsby, narrator Nick Carraway says, “In my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave me some advice that I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since. ‘Whenever you feel like criticizing any one,’ he told me, ‘just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had.’” Nick heeds this wise counsel, but until I got knocked in the dirt, metaphorically speaking, I’d forgotten it. So much of my highbrow morality wasn’t the product of amazing virtue or Christian character, but divine providence. I was holding my sons’ birth mother accountable for not being me, for not making the choices I’d been taught were right. But how could she have known without someone to guide her, to help her get ready for adulthood the way my parents had done for me?

As I sat in a dark closet in a puddle of self-pity, an even more surprising truth finally dawned on me. My anger had really been some pathetic attempt to erect a wall, a flimsy paper privacy screen between me and the fact that, with a few changes to our respective situations, she and I weren’t so different. And with that realization, my anger evaporated, and it became impossible for me to hate her any longer.

Am I still exasperated at times? Certainly. Is she the source of my frustration? Often, without a doubt. But I’ve crossed the battle line to stand with her, this woman I may never meet but who gave me two of the greatest joys of my life. We’re still walking that minefield, but we’re making progress. And thankfully a bomb in my heart—perhaps one of many—has been disarmed for good.

Illustration by John Hendrix