So if there is any encouragement in Christ, any comfort from love, any participation in the Spirit, any affection and sympathy, complete my joy by being of the same mind, having the same love, being in full accord and of one mind. Do nothing from selfish ambition or conceit, but in humility count others more significant than yourselves.

—Philippians 2:1-3 ESV

When I went into the hospital before the birth of our first child, I didn’t know I was bringing with me a set of expectations about who she would be and how the world would treat her. And yet, when Penny was diagnosed with Down syndrome a few hours after she was born, I started to see how many assumptions I had carried throughout my pregnancy. I expected her to have facial features similar to her dad’s and mine—perhaps she would have his black hair and my round cheeks, or his strong jaw, or my big eyes. I expected her to chart an accelerated pace through her developmental milestones. I expected her to say words early, just the way I had as a child. I did not expect a list of developmental delays, health concerns, and phone numbers for social workers and early intervention therapists.

People look at her distinctive features, and they assume they know what she cannot do. They assume she cannot listen or follow directions. They assume she cannot take care of herself.

Penny didn’t walk until she was 2. Her face exhibits the marks of a third copy of chromosome 21, with an extra fold of skin around her eyes, and tiny ears and nasal passageways. The Individualized Education Plan that we work on with her teachers every year demonstrates the challenges she faces when it comes to the classroom.

Penny’s diagnosis puts her at a social disadvantage. People look at her distinctive features, and they assume they know what she cannot do. They assume she cannot listen or follow directions. They assume she cannot take care of herself. Politicians and stand-up comics make jokes about people with disabilities, as if they are not worthy of the respect given to other groups of people. Women routinely abort pregnancies when they discover they are carrying a child with Down syndrome. Kids with disabilities like Penny’s are far more likely than their typically developing peers to be sexually abused.

Penny’s younger brother and sister do not face the same challenges. The relative ease with which they tackle problems in school, try out for sports teams, and navigate social expectations has highlighted for me the advantages they received by virtue of their birth and their DNA. Our kids all received our European-American heritage. They were given the advantage of married parents. And they were born into a home with more than enough money to provide for their needs and many of their wants. Our children are what many would call “children of privilege”—children born into social and personal advantages that they didn’t earn, born into opportunities without expending any effort.

Penny—with her combination of white skin, affluent parents, and Down syndrome—lives in between the world of privilege and the world of exclusion. Her in-between status has helped me to take a different look at the concept of privilege altogether.

Our children are what many would call “children of privilege”—children born into social and personal advantages that they didn’t earn.

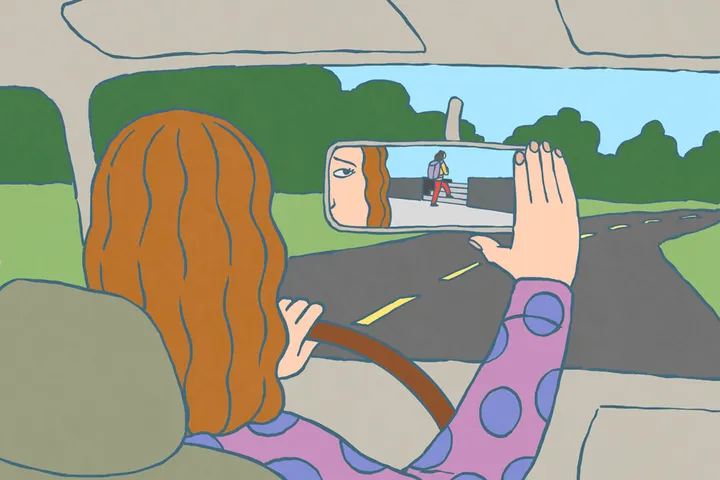

Over the past decade, I’ve learned more about the inequities between white people and people of color in our nation, as well as the inequities between people who have access to education and those who do not, and the widely divergent opportunities available to people who are born into affluent families when compared to those born into poverty or low-income households. Penny’s own social disadvantages have opened up my eyes and heart in response to the unequal treatment people of color often receive under the law and by school systems and employers. For example, I read about a study that showed people with “white-sounding” names are twice as likely to get a call back from a potential employer than people who submit equivalent resumes with names that suggest a different cultural background. I remembered the time when Penny was 2 and I called a preschool to ask whether they had any openings. They didn’t evaluate Penny. They didn’t see how she played with other children. They just heard that she had a diagnosis of Down syndrome and said, “We wouldn’t be able to accommodate your child here.” With Penny in my life, I’ve recognized the way I have gained positions of favor, not because of my winning personality or perfectionist work ethic, but by virtue of my skin color and family background.

But there is a flip side to this recognition of my own privilege and how it has operated. Living in a predominantly white, affluent, educated world has cut me off from people who aren’t as overtly “like” me, cut me off from many rich experiences and potential friendships with people of color, and cut me off from knowing more people with disabilities. Penny’s differences have brought challenges to her life and to our family. But Penny is also a gift. She is always writing notes of encouragement to people in need. She doesn’t judge others or hold grudges. She moves through life slowly, as if it is to be celebrated and enjoyed. And just as Penny’s life has helped me to see the injustice of the social divisions in our nation, she has also helped me to see the impoverishment of my own homogeneous community. She has helped me to see the advantages I have as a white person with affluence and education, but she has also helped me to see the disadvantages that come from a culture that values productivity above people, intellect above love, and individuals above community. Penny has helped me to see the wounds that come from privilege both for those who are excluded from it and for those who live within its confines. She has helped me to long for healing.

One of the hallmarks of Jesus’ ministry was healing. He healed the sick. He gave sight to the blind. He opened the ears of the deaf. He enabled the lame to walk. Jesus healed people because He cared about their physical pain and distress. He also healed them because He wanted His followers to connect the experience of physical illness and healing to the experience of spiritual separation from and restoration to God. Jesus explained His ministry to skeptics by saying, “It is not those who are healthy who need a physician, but those who are sick; I did not come to call the righteous, but sinners” (Mark 2:17).

When Jesus healed individuals, and when He forgave individuals, He also reconnected them to their communities. Jesus exhorted the Geresene demoniac to go back to his family after he was restored to himself. Jesus called out the woman who had been bleeding for 12 years and pronounced her well in front of the entire crowd around Him (Luke 8:47-48). The implication was that she was now clean and able to associate with them and worship in the temple again. Jesus’ healing was physical, spiritual, and communal. As the apostle Paul later summarized it, the ministry of Christ is a “ministry of reconciliation” (2 Corinthians 5:18), a ministry of bringing together that which seems irreparably torn apart. In our era of social divisions and identity politics, we need the healing power of God’s love if we are to find ways to mend the gaps and bind people together.

These days, it seems antibiotics and surgeries often take the place of miraculous physical healings. But we still need this deeper and equally miraculous healing that Jesus offers—this healing that connects us to one another and to God, this healing that restores relationships and communities, this healing that saves our souls and equips us for God’s work in the world.

I cannot renounce the privilege of my life, but I can repent of the ways I have used that privilege to ignore the injustices of history and of our present moment.

According to Jesus, spiritual healing begins when we repent, which, at its most basic level, means “to change one’s mind.” It means acknowledging that we are heading in the wrong direction, stopping in our tracks, and pivoting. I cannot renounce the privilege of my life, but I can repent of the ways I have used that privilege to ignore the injustices of history and of our present moment. I can examine the ways my unearned social status has separated me from other people, given me unearned advantages, and turned me in upon myself in cycles of worry and self-centeredness.

Repentance is the first, necessary condition to a larger work of healing and reconciliation. “Repent and believe the gospel!” Jesus says (Mark 1:15). As I turn away from sin, I also turn toward God. I turn toward what seems like an impossible promise—that the kingdom of God is among us and within us, pouring grace into this broken world right now.

If divisions and inequities are one illness of our culture, then acknowledging this illness is the first step and treating it is the second. For Christians, this treatment will begin with prayers of repentance and prayers of asking the Spirit to show us where and how we can participate in work that brings disparate people groups together and advocates for the vulnerable—work that honors the image of God in every human being.

I have had glimpses of the healing that could come to us if we would only acknowledge our privilege, recognize the ways it has caused harm, repent of it, and turn towards the larger reconciling work God is always doing. I see healing when I read about people with intellectual disabilities sharing apartments with graduate students. I see healing when an older white woman tells me about praying for peace alongside African-American brothers and sisters in their small and racially divided Southern town. I experience healing in my own life when I participate in a multiethnic worship service that points to the kingdom of heaven, a place where diversity will not be overcome but rather will be celebrated as an endless expression of God’s love. And I experience healing as my own daughter pulls me out of understanding human value and worth based on categories like IQ scores and college degrees and instead shows me that my value, like hers, comes from our shared status as God’s beloved children.

We will all experience healing when we recognize that the real privilege of this life is available to all of us if only we turn around and receive the unearned love of God.

Illustration by Andreas Lie